The South Seas

You never know when your life is going to change. Everyday you wake up and make decisions and those decisions lead to other decisions. You may have plans for the day but then something happens and you change your plans. Sometimes that change of plans is significant, other times it’s not. In May of 1976, a random introduction, a decision and a change of plans together changed my life.

I woke up in Camp 4 on a beautiful spring day. I had been working as a maid at the Ahwahnee Hotel all winter and now that is was climbing season, I was back to being a C4B (Camp 4 Bum). A friend from New Hampshire, Paul Boissonneault and I were discussing plans for the Direct North Buttress on Middle Cathedral when someone I had met a few days earlier walked into our campsite. It was Max Jones.

“Hey, my Nose partners just crapped out on me, are you still looking for a partner? Do you still want to do the Nose?” He asked.

I didn’t really know Max from Adam, as Spencer Lennard had only just introduced us a few days before. “You guys ought to climb together,” Spencer said. Max and I shook hands, and each mentioned our plans for the Nose later in the month, and didn’t think too much more about it.

In spite of planning for the DNB with Paul, Max and I decided to drive down to the El Cap Meadow to see how crowded the Nose was, and get an idea how soon it might be open. Even back then, it was still a popular route, and you often had to wait your turn. We saw that no one was on the route, but that there were ropes fixed to Sickle Ledge – P4 of the Nose. Since we had both climbed to Sickle recently we didn’t feel the need to climb those pitches again, and it was our eventual plan to just jug those ropes. It was common back then for semi-fixed ropes to be hanging from Sickle all season. For some reason we decided to gather some gear, pack a bag and spend that night on Sickle. We drove back to camp and I went off to the grocery store for some wall food. Along the way, I ran into my girlfriend, “I’m going up on the Nose today with a guy named Max”, I told her.

She asked me all the usual questions. “Who’s that? Do you know him? Is he safe? Is he any good?” I had no idea of the answers, so I guessed: “Yeah, he’s good, he’s safe, he’ll be fine.” I didn’t really know about any of those things, but for some reason though, I felt it would be all right.

The rest, you could say, is history.

We both had the same love for long free climbs and it wasn’t long before we had climbed early free ascent of routes like the Rostrum, Astroman, Crucifix and others, all among the hardest routes of the day. We developed the “free as can be” attitude and went up on routes like the South Face of Mt Watkins and Salathe Wall with only a free climbing rack. We treated those routes like long free climbs by leading and following every pitch.

Aid climbing was a different discipline that we both enjoyed and we climbed early ascents of the Mescalito and Zodiac together. An early attempt on the Pacific Ocean Wall ended when a large flake I was nailing fell off, crushing a finger on my right hand.

We drifted apart after 1979, and I was starting to feel that “I had sort of done it” in Yosemite. I spent a few years climbing, but nothing compared to what I did with Max. In the early 90’s, he and I independently got into sport climbing, but after spending fifteen days to redpoint a single pitch, I realized that I needed to get back to my roots and climb long routes with gear, even if those routes were considerably easier than my sport climbing ticks.

I never had a partner like Max again. Climbing with Max was like climbing with your dream partner – he never got sewing machine leg, never took too long on a pitch, never backed off a pitch, never bitched or moaned or wanted to bail. We both had the same level of commitment and desire, and we got along really well.

In 2009 I felt inspired to start climbing in Yosemite again, and was soon drawn back to El Cap. I discovered that whenever I was telling someone about my rock climbing, I was really telling them about climbing El Cap. I figured I should just go climb El Cap, and of course my thought was that I should give Max a call to see if I could get him to climb with it me. Initially, he didn’t seem too interested, but I kept sending him photos and links to my trip reports. I was sure to emphasize the “fun” and “comfort” part of my ascents. After my solo of Grape Race/Tribal Rite, I was surprised to hear that Max had been in the Valley with his family while I was up on the wall. I knew Max loved being up on El Cap as much as I did, and was happy to hear that Tom Evans had pointed me out to him. I hoped Max would feel at least a little bit jealous. Of course, after climbing the route, I bombarded him with photos heavy with comfortable ledge shots, a hanging stove brewing coffee, warm sleeping bags and me smiling and having a lot of fun. I sent him even more photos after I climbed the Shield in the fall of 2010, and I told him that I’d totally take care of him on any route he wanted to do. I’d supply all the group gear and give him a list of things to buy and how to prepare. He wouldn’t even have to drive; I’d pick him up on my way to Yosemite. All he had to do was to be psyched and be in shape, which is not hard if you’re Max Jones. Anyone who knows him knows he’s a friggen animal, and that once he puts his mind to a project, it’s as good as done!

Finally late last fall, I got the email I had been dreaming of – Max agreeing to climb El Cap with me again! He wanted to do the South Seas, to sort of finish off our vendetta with the Pacific Ocean Wall.

I immediately started sending Max “tutorials” and lists for anchor building, hauling, clothing, food, and equipment. Max had never clipped into a 3/8” three-bolt belay, had never slept in a portaledge, and had never climbed an aid pitch using only cams and nuts. I knew it was going to be a steep learning curve for him, but I was confident in his ability to figure it out. Max and I always got along so well because we both share a “can do” attitude, and are pretty sure we can figure out what to do when we need to.

My plan was to drive to Max’s home in Carson City from Hood River, load his gear into my car and then get up early the next morning, drive to the Valley, hop out of the car, march to the base and fix the first three pitches, Max leading the first and third, then hump, haul and blast the next day.

Max was psyched and had been doing some research about the climb, and he sent me some questions about the first pitch: How hard is it, how overhung is it, would he be able to place pins on it or is that not allowed any more? I was beyond totally psyched, and was viewing that pitch through the prism of my three recent El Cap routes. I am fully comfortable in my steps these days and fluent with my multi-colored, multi-shaped, and multi-size rack, a rack that was barely a gleam in an engineer’s eye when Max had climbed his last El Cap route in 1979.

It took me a while to realize that my excitement might mean our downfall. I started remembering how I had pushed John Fine almost to the point of exhaustion on our 2009 Shield attempt. I started doing the math of driving to the Valley and hiking to the base, then factored in the short days of the fall season. I don’t know why I felt the need to climb the route so quickly, I had come to enjoy a modest level of “big wall camping” but here I was, planning a virtual speed ascent of the route. I came to realize that I was planning too much work for the first day and that I shouldn’t rush it. I wanted it to be fun for Max and so I tried to relax the schedule.

Max and I hadn’t spent too much time together since '79. I’d see him at Donner or Cave Rock when I’d go down for a climbing trip and he came up to Smith Rock once, but the last time I saw him face to face was at his sister’s wedding 11 years ago. At the time, his daughter was seven and mine was four. Interestingly, we both seemed to have followed similar paths in life. We both lived for our sports, both worked for ourselves with our wives, both have beautiful and wonderful daughters, and both had lives that could only be described as “casual”.

The years of my life I spent climbing with Max have always been a special time for me. I was young, I was fit and I had a little bit of talent that allowed me to look at any line, and think “Wow, that looks cool, let’s go climb that"! I know Max felt the same way and we were always amazed and appreciative that we had the freedom and ability to go live our dreams.

On Friday morning, I left Hood River for the ten hour drive to Carson City. Patti and Caitlin, Max’s wife and daughter had to be at a soccer game in Fresno early on Saturday and were planning to get up early for the drive. Max and I would get up along with them and leave for the Valley.

On the drive down the East side to Tioga and we talked about our business, our daughters, our wives and our lives.

Whatever my feelings were when we rounded that last corner and El Cap came into view, they were probably quite different from Max’s. I felt excited and ready to go. I wasn’t thinking for a second of gear placements or trying to remember how to set up my jugs, or how hard it would be or how I would react to being way off the deck with a tiny rack of pins (compared to a ‘70s era rack of 65 to 90 pitons) and an incomprehensible cluster of spring-loaded widgets of all shapes, sizes and colors. Max was probably worrying about how much he knew of big wall climbing would be obsolete and useless.

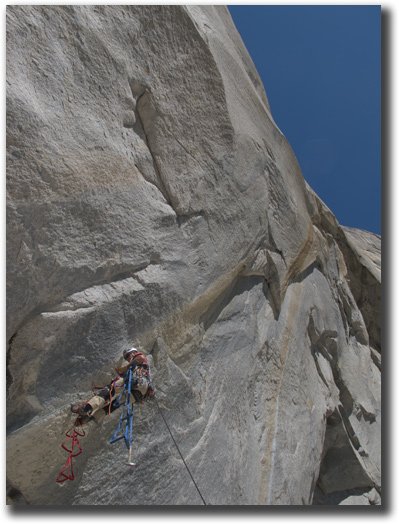

We reached El Cap Meadow, hopped out of the car, talked to Tom for a bit, then grabbed our packs and headed up to the base of the climb. Of course, I had sent Max a photo of the first pitch. The only trouble was that my photo had made the pitch look far less overhung than it actually is! Max had done some research on it so he wasn’t too surprised by its steepness. He was putting on a good game face.

We got into our harnesses and I handed him the suggested rack. He looked at it like I had just given him a camel tongue and then told him that if he put it between his butt cheeks, it would give him super powers. After a few minutes of wandering around the start he got on it, placing a beak, a cam, then clipping a few rivets and a fixed pin. The time stamp on my photos show forty minutes for the first five or six moves, and for the first time I was questioning my wisdom of sending him up on this pitch. But he was sounding happy up there, he’d look around every now and then and I could see him working with his aiders, trying to get the hang of it again. I could see him gather the whole rack up in his arm and stare at it as if someone had just given him the Dead Sea Scrolls and expected him to read aloud from them. He was making progress – it wasn’t fast but at least it was progress – and I tried to be upbeat and encouraging. Every now and then I’d tell him he was doing great and how cool was it to be back together on El Cap. Ranger Ben came by and mentioned that the first pitch was the steepest and most awkward on the route and that if Max got up it, every other pitch on the route would pale in comparison. I was so glad for Max to hear Ben’s words of encouragement that that if Ben had been closer, I might have been tempted to give him a big hug and kiss on the lips. I could tell Max was having a good time when he stopped to photograph some kids who were trying out the Alcove rope swing, and at about 4 o’clock – after about five hours – he reached the anchor.

I knew the day was getting short, so I tried to clean the pitch as fast as I could. I took off on the second pitch – it only took me about an hour to lead – but by the time Max started cleaning, it was already dark. I was so mad at myself and sorry for this hellish day I was putting Max through. First of all, he was leading on a totally unfamiliar rack, most of which hadn’t even been invented the last time he climbed El Cap, and now I was forcing him to clean an overhanging pitch that traversed diagonally off to the side, in the dark, with no headlamp.

Max seemed calm though. I repeatedly told him that I was sorry and that the rest of the route would be different. When he arrived at the anchor, I had the brilliant idea of having him clip his Grigri into the lower of the two ropes that I had tied together to reach the ground. That way, I’d lower him on the upper rope till it came tight to the anchor, and then he could lower himself the remaining distance to the ground. I hoped it would save him the effort of dangling on a free hanging rope and trying to pass a knot in the dark. My plan worked perfectly, and soon we were stumbling our way down the trail and driving to Upper Pines for dinner with our families.

I wished I had called it a day after the first pitch. After all, I had told Max that it would all be fun and that I’d totally take care of him. Yet I sent him on a hard task the very first day. What was I thinking? Clearly I was failing as a “big wall host”. I resolved to be more aware of our fun to suffering ratio and to err on the side of fun for the rest of the climb.

My modified plan was to casually hump loads to the base, jug to the top of our ropes, haul, and then either camp there at the top of 2, or else climb one more pitch and camp at the third anchor whichever Max wanted to do. Peggy and Ellen had to leave early to drive to Reno and catch a flight home to Hood River, but Patti and Caitlin carried some gear up to the base for us, and then left when Max and I started up with our second load of the day.

The weather report was for clear weather for the foreseeable future, and although the day before wasn’t exactly an auspicious beginning, I could sense that Max was determined and positive. He got started on the 230-foot free-hanging jug as I packed the bags. We hadn’t gotten an early start but I wanted the day to be casual with plenty of sitting around time for Max. After I jugged the line, I hauled and set up the ledge. We were well settled in when the moon rose over Sentinel Dome. I could see Max start to relax and get comfortable with his new surroundings. His next pitch in the morning lay recumbent above us – an easier ramp – everything that the first pitch wasn’t. I made it a point to show that to him.

The morning breakfast menu was cereal and hot coffee. BIOD (Back In Our Day) waking up on a wall was always uncomfortable; more often than not the cold had seeped through the thin fabric of your hammock and through the compressed insulation of your sleeping bag. Coffee was not on the breakfast menu nor was cereal with milk. Breakfast usually consisted of Pop-Tarts, cheese, and cookies, whatever you could find in the haul bag. Your hips were crushed from the hammock tight around you and from lying against the rock all night. You probably had slept in your clothes since taking anything off was near to impossible. Everything was pressing against you, your harness, the hammock, and you against the rock until you climbed to even the tiniest ledge or were off the climb. Max and I shifted our foam pads, pillows and sleeping bags so we could sit up, backs against the cliff and face the Valley, then we ate, shot some video, talked about life, climbs in the past, and pitches in the near future.

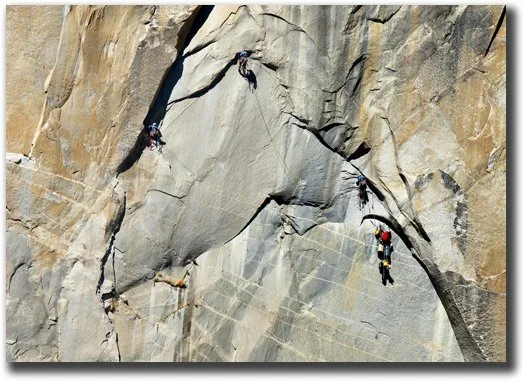

My plan was to have Max lead both the third and fourth pitches. I wanted him to have a good experience and get a few more pitches under his belt. He would have to set up his first wall anchors and then use my 2:1 Hauling Ratchet. We had gone over hauling the day before, but he had never set it up and made it work by himself. I wasn’t too worried because I knew Max was quite like me in that regard. If it wasn’t working correctly, he’d look at it and simply figure out how to make it work. He led the third pitch in much better time and was soon up on the fourth pitch. We had noticed earlier that the weather report had gone from “clear and sunny for the next five days” to 20% chance of rain that day and 40% that evening. We could see the rain moving in from the east, so we both suited up in rain gear and got ready for some wet climbing. I guess it might have been wet if the wall didn’t overhang so much above us, because we stayed totally dry. I couldn’t really see a rain line, but I could easily see the climbers next door on the N.A. Wall getting soaked.

Max worked diligently on the pitch and I don’t think he ever even turned around to notice. I was glad that although we would only climb two pitches that day, Max could enjoy some more reasonable climbing that was different from the first pitch.

As I was setting up the ledge, the clouds completely enveloped us. It was eerie sitting there, not being able to see anything further than seventy-five feet in any direction, and it felt as though we could have been on the moon. It had stopped raining for the time being, but since the forecast was still calling for rain we hung the ledge under the fly.

The next morning I silently laughed at myself while I arranged the rack for the crux of the route, the 5th pitch. Years ago, looking up at the South Seas from its base had been a factor in the termination of my first rock climbing career. I had still been freaked out about the flake on the Pacific Ocean Wall, and looking up at the overhanging South Seas, looking up into the unknown, to hidden flakes behind every corner, was more than I could handle.

Now on a perfect sunny day, I was eager to climb it and moreover, to see if I could climb it with no fixed gear at all. But that dream died a quick death. The first move was an unavoidable circlehead driven up underneath an overlap, and the second move was a beak I had to hammer.

After that though, I had a great time, I avoided all of the fixed heads on the pitch and climbed it sans fixed gear. Max was having a little problem with tangled ropes and his jugging set up, so it took him a while to clean this diagonaling 5th pitch.

Max’s next pitch was straight up a beautiful clean orange corner, and I knew he would enjoy it. It ends in the middle of a bolt ladder, and we were set up on the ledge and eating by the time the moon came out that night. But I was becoming a bit concerned about our water supply. I had planned for six nights on the climb, plus one on top and then one additional day’s worth in case of emergency. At our present pace of two pitches, a day it looked as though we could spend nine days on the climb, and unless we really started to conserve water we would run out. I didn’t make my concerns known yet; I was just hoping we would speed up a little.

By now we had established a rhythm to setting up and taking down our vertical campsite. I’d set up the ledge and get it arranged to the correct height relative to the haul bags. Max would arrange the rack for the next lead and stuff the ropes into their bags. My technique is for the haul bags to always be on the left of the ledge, and then have the ledge so it hangs about six inches below their bottoms so that I can easily stand on the ledge and empty them. We each had our own haul bag, hung side by side, to make things easy to find and put away. After getting the bags unpacked, we would then take off our harnesses and put on a loose swami clipped into a dedicated “night sling” hanging from the ledge anchor. After that, we pulled out foam pads, clean socks, sweaters, sleeping bag liners, iPod and speakers for music, a bit of gorp as a pre-dinner snack, Advil for the pains of the day and cell phones for checking the weather and calling our families.

I’d then get some water boiling for dinner, which usually consisted of a backpacking dehydrated meal, far better than the cheese, crackers and fruit cocktail we would have had BIOD. Then we’d settle back to talk about the day and the route while we watched the light fade from the Valley and waited for the stars to appear. Frequently at that time of day, Max would get a faraway look in his eyes. It was like he had gone back in time and was looking at an old scene he had never expected to see again, and he didn’t understand how or why he was able to see it now. It was old but it was new, something he had said goodbye to, but now here it was back again. Maybe he was thinking, “is this climbing going to grab ahold of me again? How is this going to work out? Am I going to want to do this again? Hell, am I going to even be able to finish this one?” I knew he was considering all the angles, like the water issue and how slow he was going how he could he pick up his pace. I knew he could feel it all coming back, but that it was sort of like hiking through knee-deep mud – you knew you could do it but every step was a struggle.

Max and I always had a good, friendly level of competition between us; it’s what pushed us to be the great team we were back in the 70s. On South Seas, Max told me that he had timed me when I reached an anchor and that one minute after getting there, I yelled down that I was off belay and that the lead rope was fixed for jugging and cleaning. One minute later, I would be pulling up the haul line, ready to haul. He therefore set these times as a goal for himself when he reached his next anchor. He also told me that as he was nearing the anchor, he’d review in his mind what he was going to do as soon as he got there. When I was leading, Max would focus on leaving the anchor as soon as possible. I’d give him a “25-foot warning,” and then he’d start putting stuff away, getting his rack on, and being ready with his jugs. He also remarked on how I hardly ever used a daisy, and that he felt he wasted too much time untangling and adjusting them. I reminded him of the “rest step” where you put one foot in a high step, drop your knee and tuck that foot underneath your butt. This puts you in a comfortable, secure, hands free position. I then described how I try to “free climb” in my aid slings by staying balance and climbing right to their tops every time and getting into my rest step, leaving me locked in quickly and easily.

The days in the fall are certainly short and the pitches on South Seas, for the most part, are long. The route is a connection of fairly large features that seem to go on and on. My first pitch the next day – the “Great White Shark” – is 150 feet long and the next one – the “Rubber Band Man Pendulum” – was billed as being 130 feet although it seemed a lot longer with the penji. The initial climbing is a beautiful and easy bolt ladder that leads up to The Shark, a corner that follows a widening crack to the belay. I yelled down to Max that if I were Tommy, I’d free climb it, but that since I was not, I was going to have fun aiding it. It was on this pitch that Max and I solved his jugging and cleaning problems. It was funny having to explain to him the basics, because I knew it would immediately become second nature to him the instant the words came out of my mouth. He had about 25 feet of the Shark left to clean after we talked about the proper setup, and this was the last time he ever mentioned it.

The topo mentions A2 arrows on the pendulum pitch, and Max thought that having them would maybe speed him up a bit. Since he was unfamiliar with the newfangled gear, he was getting a bit frustrated looking at the rack and trying five or six different pieces before finding the right size. I didn’t mention that I frequently go through as many choices but only faster. The section above the anchor shows C2 and then A2+ knifeblades but Max climbed it all clean on tiny nuts and cam hooks.

He was happy to have climbed that section fairly quickly and was soon lowering down for the pendulum. He ran back and forth as I lowered him, and then easily stabbed a flake and started to climb back up to the pendulum point, back cleaning as he went. I was comfortable in the Belay Lounge, a sort of full body belay seat that supports your back and neck, when all of a sudden the rope came tight and I realized that Max had fallen. He had fallen down almost even with me, but told me that he had had the foresight to leave some gear as protection before getting too far above the pendulum point. He figured he went thirty feet, but would have gone sixty if his pro hadn’t caught him.

He climbed back up, placed a couple of beaks, a couple of Lost Arrows, and many dicey small nuts and cams. When I cleaned the pitch I was amazed at all the gear I took out of it. He hadn’t placed more than normal, it just seemed the pitch went on forever and he had placed a lot of gear. I didn’t notice it right away, but it seemed like Max almost came back to 100% of his old self on that pitch.

Off to the right of the anchor were two bolts with thin welded rings as hangers that looked better suited to hanging plants from then for an anchor. We laughed at them, but I equalized them with two slings and we hung our ledge off them anyway.

That evening we stayed up late talking about our businesses, our families, and our lives. It wasn’t uncommon to have long pauses in our conversation. I’d look over at Max and he’d be staring out at the stars, the wall and the Valley, still looking like he hadn’t yet quite come to believe where he actually was.

Waking up on a wall used to be the worst part of the day, but these days it’s like waking up in Disneyland. Hot coffee, breakfast in bed, a room with a view and once you’re ready to go, an E-ticket ride for the rest of the day! I led a 140-foot pitch and then Max combined two pitches, one supposed to be fifty feet and the other supposedly a hundred. Basic math will tell you that 50 and 100 add up to 150 but the linked pitch took 90% of my 65-meter rope. I don’t know how it did that, it just did. The pitch was certainly as involved as any I’ve climbed in my latest El Cap climbing craze, and it kept Max’s interest right till the very end. It was the classic “take everything and use it all” kind of pitch – tiny nuts, giant cams, hooks and everything in between. Max was beat by the time he finished it, and given that the next day was forecast to be hot, we inventoried our water and formulated a plan.

At only two pitches climbed a day, it looked like we might have five days left on the wall, but a couple of the pitches were short, and three others were mostly free or all free so we figured they would go quickly. At best, we could finish in three and a half or four days and hopefully find water on top. At worst, Max had purifying tablets and we could run down to Horsetail Creek for water.

The lower part of the Black Dihedral loomed over us that night. We could see a few copperhead wires on the skyline and were excited to get up there.

We got our earliest start the next day, as I wanted to link two pitches that would total 170 feet. Both pitches were rated A3R so I was ready for a good fight. Right off the anchor was a sad collection of welded and buried RURPs, some with wires, others without, and no way to avoid or remove any of them. Next was an easy blocky section that I was able to free/aid quickly. The topo showed “bad rope drag” when combining the two pitches, so I lowered from the intermediate belay anchor and cleaned most of the pitch. Turning the corner onto the Bearing Straights and clipping the fixed heads was fun but seriously lacking in any challenge.

I thought back to when Max and I had attempted the P.O. in 1978 and how fun it would have been to have placed those heads myself. When Max cleaned it, he said clipping fixed heads had all the fear of using them but none of the fun of placing them. With all the fixed gear, Max was able to clean the pitch fairly quickly and it looked like we might be on schedule for a three-pitch day. Max, noting the “C4 or A2” of the next pitch, grabbed some pins and commented before taking off that “any pitch rating that has a ‘4’ in it is your pitch, Hudon.” Further up, after placing three of the pins, Max came up with the line that pins are just like Crack – once you start using them, all you want is more. It seemed like having the pins really relaxed him. He had been getting frustrated trying to find a nut or cam that fit, and figured it was legit that after five or six attempts he could place a pin. Even so, he didn’t place more that four on that pitch, and no more than ten in the entire route.

The evening before we had tried to figure out how long the third Bearing Straights pitch was. The printing on my shrunken topo was a bit soft and it could have been 100, 120, 160, or 180 feet. We laughed at each other trying to read it; we’d polish up our glasses, give it a serious look, and take our best guess. Max even took a photo of it with his iPhone and then zoomed in on it to try to decide. We agreed that it said “120”.

It was just three in the afternoon when I started up the third Bearing Straights pitch. This would be our first three-pitch day, and we were doubly happy that the forecasted 80-degree temps had never materialized. In fact, some high clouds had blown in and it was quite nice. Max and I joked at how long the pitch would really turn out to be – it didn’t look too long but I couldn’t see the anchor either. I told Max to time me on it and that I was going to speed climb it, but the slow burn of the heat and the long burn of the pitch, all one hundred sixty feet of it, did me in. It was one of those pitches that required a lot of gear, and although it’s rated only C1 or 2, it seemed like there weren’t too many “gimme” placements. I was pretty beat after hauling and was glad that we had flagged the ledge all day, since all I had to do was clip it into the ledge anchor (this time a plant hanger bolt and a rivet) and then flop down on it.

That night I told Max it was a bit spooky how easy and relaxed I felt being up on El Cap with him again. Max and I had always been naturally efficient on any climb we did. Our El Cap ascents in the 70’s were usually the fastest ascents of the day – not because we were trying to go fast, but more because we were so efficient. Here we were, 32 years since our last El Cap route together, but that efficiency was still there. Max was rusty, but the communication between us hadn’t changed.

Max’s first pitch the next day was billed as only “60 feet” but we laughed that it could be anywhere between fifty and several hundred feet long. It ended at the only ledge on the route so far, and below the Black Tower. Looking up at the wide crack behind the Tower I stripped down to free climbing mode, grabbed only a few cams and then took off. The topo shows “5.8 R” with ledge fall potential but all the holds seemed big and it didn’t seem to be any big deal. Our large cams fit into the crack well and I diligently tried to keep myself out of the clusterfuck that wide cracks can be. I was happy to climb the 140-foot pitch in 20 terror free minutes, guaranteeing another 3-pitch day and relieving the stress on our diminishing water supply a little bit more.

By now, Max was feeling at home in his aiders and getting more familiar with our rack of cams and nuts. On just about every pitch he led, I found some ingenious or novel nut or cam placement he’d made. I thought to myself, “Dang, it’s nice to be climbing with Max again”.

He took a normal amount of time to lead the pitch and we again set up our hanging camp, this time from four solid 3/8” bolts and a couple old 1/4" bolts, one of which we removed in an attempt to clean up the area. Again it was a beautiful night and we found ourselves talking about life till late in the evening.

The next day I led off a fun C3 pitch that I climbed clean-clean aside from one hammered beak at the beginning, and I avoided three or four heads which Max took out. I easily linked the next pitch since it involved only connecting a wandering bolt ladder and a long horizontal ledge. Max led a slightly diagonal, slightly dirty but not bad pitch to an area named the Highbrow Bivouac. We thought the area had been misnamed since hanging a ledge from the bolts or sleeping on the jumbled area below the anchor would be awkward at best. I free/aided the next pitch, happily using the holds cleared out of the grass by Levy, Jordan and Adam a few weeks before. The pitch ends at a flat wall with a two-foot-wide, twelve-foot-long ledge below it.

We were sure this spot was what should have been named the Highbrow Bivy. It was the perfect spot to spend our last night on the wall.

On our last day I led a fairly long, grassy but not un-enjoyable free/aid pitch to a rare, totally climber-built anchor. There was a 3/8” bolt and three plant hangers (with elongated rings) about ten feet off to the side as an alternate anchor. If I had had the time and the tools, I would have removed that whole anchor. Max’s last pitch was an awkward affair up a steep corner and then up and through some overlaps to the top. Dreading horrendous rope drag, he went to great lengths to ensure the rope ran smoothly, at one point clipping ten biners together since he had run out of slings. He hauled and after cleaning the pitch we began to ferry everything far from the edge to a nice bivy spot.

I don’t know about Max, but I was feeling quite emotional right then. I was looking at Max, looking at all the gear, looking at the top of El Cap and the Valley and seeing all the other times we had been there, after the Nose in 1976, Mescalito and Zodiac in 1977, the Salathe free attempt and West Face in 1979, and then the Nose again in 79. I had grown up on this cliff, and I had grown up on it with Max.

Max and I had the tradition of shaking hands and taking a team photo after every major route. At the top of the South Seas we diligently moved all the gear well away from the edge and removed our harness before shaking hands and taking the summit photo.

We had only a gallon of water but Neil and Callum, fresh off Reticent, walked by and told us they had left five gallons on top. We headed up there and ran into Tommy T and Jenn finishing New Dawn, and we talked as Tom ferried gear from the last anchor to the summit.

At one point he was rapping back to the anchor but stopped and looked at Max. “So Max, you said it was great, but do you want to do it again?”

I froze, that was the question I had been burning to ask him for the last two days.

“Oh yeah, I sure do”! Max replied.

Overjoyed, I uttered a silent YES!

Sometimes you don’t know when your life is about to change, sometimes you do.